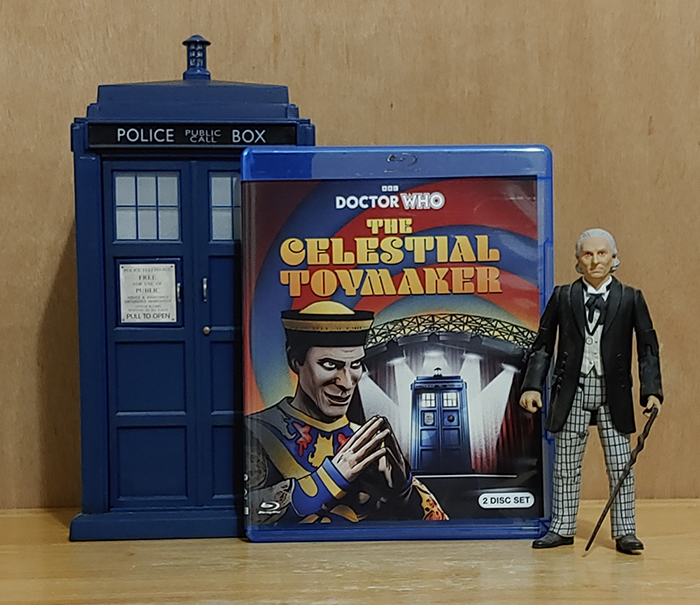

While I’m recovering from surgery, I’m on strict limitations about how much weight I can lift and I am trying to strike a balance between moving around enough to restore my range of motion but stay calm and quiet enough that I allow myself to heal. Of course one of the best ways to get me to sit for a little while and take it easy is put on a good movie or TV show. By good fortune, the BBC released it’s BluRay of the Doctor Who episode “The Celestial Toymaker” on the day of my surgery. My wife kindly ran out and picked it up two days later. This episode goes all the way back to 1966, near the end of William Hartnell’s time portraying the Doctor. The Doctor’s companions are Steven Taylor played by Peter Purves and Dodo Chaplet played by Jackie Lane. The titular Toymaker was played by the legendary Michael Gough, who has portrayed characters ranging from Arthur Holmwood in Hammer’s Horror of Dracula to Alfred the Butler in the Tim Burton Batman films. This is one of the “lost” episodes. Only the fourth episode of the four-part serial exists in its entirety. So, the episode was recreated using 3-D animation from Shapeshifter Studios. On the BluRay set, you can watch it in full color or in black and white, as the episode would have been when originally aired.

Interest in releasing “The Celestial Toymaker” has been high, since the Toymaker’s return in Doctor Who’s 60th anniversary special “The Giggle,” this time with Neil Patrick Harris playing the Toymaker. That said, the Toymaker had originally been slated to appear in an episode with Colin Baker in the 1980s, but the episode was scrapped when the series went on hiatus. Fortunately, Big Finish adapted the script for audio and you can find “The Nightmare Fair” at: https://www.bigfinish.com/releases/v/doctor-who-the-nightmare-fair-421. My interest in the character came from seeing productions stills of the episode in a book about the series. The episode featured creepy clowns, surreal sets, living playing cards, and, of course, Michael Gough. I’d long wanted to see it.

The story’s premise is pretty straightforward. The Doctor’s TARDIS is pulled into a mysterious region of space controlled by the Toymaker, who offers the Doctor and his companions a challenge. If the Doctor and his companions succeed at a series of games, he’ll give them control of the TARDIS and they can leave. If they fail, they’ll essentially have to spend the rest of their lives in the Toymaker’s domain as his toys. The Doctor is given a complex logic puzzle called the Trilogic game, that he plays throughout the four episodes. In each of the four episodes, Steven and Dodo must play somewhat simpler games against the Toymaker’s toys. In the first episode they play Blind Man’s Bluff against a pair of clowns. In the second episode, they play against the king and queen of Hearts to find the one chair out of seven that won’t kill them. In episode three, they must find a key and find a way to dance across a floor of killer ballerinas to open door, and finally, in the fourth episode, they must play a game of hopscotch. The catch, if they step off the squares, they’ll die. At one point early in the first episode, the Doctor annoys the Toymaker and is turned invisible and mute. This actually allowed William Hartnell a two-week holiday during the episode’s filming. Interestingly, the production team had discussed making him return to visibility as a whole new actor, which would have made the regeneration narrative that ultimately was developed to explain actor changes a lot trickier down the road.

Because we do have one episode of the original and lots of still photos, we can get a sense of what the episode was like originally. The recurring toys were played by Carmen Silvera, Campbell Singer, and Peter Stephens, all popping up in new costumes each episode. The sets were fairly bare with just enough “dressing” to allow the actors to play the games. In the animated recreation, they went full-out and visualized twisting, large, surreal worlds. Blind-Man’s bluff was played on a gravity-defying stage where up and down, left and right changed depending on where in the game you were. The hopscotch game involved floating triangles and a misstep would mean a bad fall as well as electrocution. Overall, I thought the animation allowed the Toymaker’s world to come to wonderfully, creepy life. The character animation was quite good and fluid, and quite convincing in long shots. Animation allowed the toys to look like living toys rather than actors in fancy dress. My only real issue with the animation has to do with the way they chose to “paint” the characters. There were sharp tonal contrasts on the faces and hands with almost no gradient or blending between colors, giving the characters’ hands and faces a blotchy look. Shadows on faces sometimes made the characters look more like they needed a shave. Some characters looked like they had rather serious skin conditions on their hands. That noted, the contrasts work better in the black-and-white version than the full-color version.

One interesting historical aspect of this episode was the decision to dress the Toymaker in Traditional Chinese robes. Despite that, the makeup artists never gave Michael Gough the usual “yellowface” makeup that would have gone with a white actor playing an Asian role. At times, I felt like Gough was doing a very mild Asian accent. That said, Gough was actually born in Kuala Lumpur when Malaysia was a British Colony. So, now I’m even less certain he was doing anything deliberate with his accent or voice. I suspect the writers did literally mean “Celestial Toymaker” in the sense of a Toymaker with grand, cosmic powers. However, being the 1960’s, I wonder if the costume department thought “Celestial” in the sense of China as the “Celestial Empire” and brought over Chinese robes. Since money, time, and budgets were tight in those days, plus having a Toymaker who could literally wear whatever he imagined wearing, I suspect the filmmakers just rolled with it. A more problematic issue occurred in the second episode of the serial. At one point, the King of Hearts mutters the traditional “Eeenie Meenie Minie Mo” rhyme using a racist slur. In the new BluRay release, they seem to have wisely excised that part of the mumble. I don’t feel anything was lost with that.

If you like stories about great cosmic beings putting humans into surreal environments, you might also enjoy my novel Heirs of the New Earth. You can learn more about it at: http://davidleesummers.com/heirs_new_earth.html.